Tabasco Sauce: A deep dive

On the little bottle that conquered breakfast (and lunch and dinner and dessert)

I WAS IN LONDON recently when I stopped off at a branch of Chipotle (a multinational Mexican fast food chain, IYKYK) for a hot honey chicken salad. After the server handed me my tray of food, I found a table in the corner and placed the tray down, and then went over to the area where they provide napkins, cutlery, and condiments, and naturally grabbed myself one of the numerous bottles of Tabasco Sauce that were readily available for customers to use.

Ten minutes later, having doused my salad a’plenty and wolfed down mouthfuls of grotesque proportion, I began to relax enough to start noticing my surroundings and was struck by just how clean the Tabasco bottles were. They were so clean they looked as if they had just been recently polished. It is a rare thing indeed, I thought, to find so many squeaky-clean condiment bottles in such frantic fast food restaurants in cities like London at such late hours. And I found myself imagining that it was one of the daily or perhaps twice-daily tasks that the staff members at Chipotle dutifully completed: polishing the Tabascos.

It was then that I realised there were no other condiments available in Chipotle at all; just Tabasco, and I considered trying to calculate how many Chipotle branches there might be across the globe, and how many bottles of Tabasco sauce that might roughly equate to. As I threw my fork into my newly-emptied cardboard bowl and wiped my tingling lips with my napkin, I reflected on what a lucrative deal that must have been for the Tabasco company to strike, among many, and I marvelled, not for the first time, at this brand’s unmatched reach and success.

How had this company gotten their little bottles of pepper sauce into so many hearts and so many minds?

A book, a podcast, and a Perplexity deep research prompt later, I was ready to begin writing, all the while wishing I’d taken a picture of those shiny bottles in Chipotle, just so I could show you how finely polished they were.

I was determined not to get bored writing this piece by turning it into a dry historical survey. So instead I have committed to giving you just a dash of what I think are the most interesting ingredients in the story of how these ubiquitous red bottles came to be so well polished and placed so prominently inside our cupboards and our pantries.

I’ll start with a brief and factually patchy summary of the company’s origin story. I’ll look at Tabasco’s iconic design and military connections. And I’ll end with the surprising, personal, and unconventional ways people around the world have expressed their love for it.

This is my deep dive on Tabasco Sauce.

The bankrupt gardener

The Averys were a wealthy family from New Jersey who made their fortune in sugar production (yes, slavery I’m afraid) in the early 1800s. As part of their business assets, the Averys bought an island—roughly the size of New York’s Central Park—located in the swamplands of Louisiana to house a new sugarcane plantation. They discovered that the island, by now renamed Avery Island, wasn’t actually an island at all, but a massive salt dome that was slowly rising from the marshes. By mining and selling the salt beneath their feet, the Averys combined these profits with the profits already being made from sugar, further bolstering their wealth and social standing among the U.S. upper class. The Averys operated these businesses until the American Civil War put a stop to them in 1861.

While all this was going on, the McIlhenny’s (mack–ill–henny’s) were a middle-class Irish-Scottish immigrant family who owned a tavern in Hagerstown, Maryland. When John McIlhenny, head of the family, died of cholera on his son Edmund’s 17th birthday in 1832, the boy Edmund was forced to quit school and start working to take care of his mother and seven younger brothers. Edmund went into accounting and, cutting a mightily long story short, by the time the civil war broke out three decades later, he had become a wealthy New Orleans bank owner in his own right. Crucially during this time, Edmund had also met and married Miss Mary Eliza Avery of Avery family fame, thus forever forging a formidable family business alliance.

However, when the civil war broke out, a crumbling credit system, massive currency inflation, and widespread defaults—not to mention the Union’s capture of the economic hub of New Orleans—sent the precocious Edmund McIlhenny swiftly into bankruptcy. With no other option, he was forced to move in with, and become financially dependent on, his in-laws on Avery Island.

This did not sit right with Edmund McIlhenny. Here was a 50-odd-year-old successful financier who’d overcome the death of his father, saved his family from poverty, and managed to marry upwards into one of the most influential families in the state, who suddenly found himself having to accept handouts.

This was the moment Edmund chose to begin making pepper sauce, of all things, and nobody—not even the professional historian, Mr. Shane Bernard, who has written a book and spent 25 years compiling the McIlhenny Archive—knows why Edmund started playing around with peppers. Some say he met soldiers in the streets of Louisiana who recommended pepper sauce as way to spruce up bland local grub. Others say he was explicitly searching for a new business venture to reclaim his independence and had noticed how cheap-to-grow, popular, and thus potentially profitable peppers might be.

One thing we do know is that, whilst Edmund was figuring out what to do next, he was spending a lot of time tending the Avery’s garden. He kept written records of all the cabbages and lettuces he was growing. No mention of peppers. But it’s safe to assume he was probably growing those too. Whatever it was that first possessed Edmund McIlhenny to make pepper sauce and sell it to the public, the fact is that my table, your table, and tables in Chipotle the world over would be bereft of Tabasco Sauce were it not for the American Civil War and a ruined banker with a green thumb.

I really wanted to bring this first part to a close with a pithy paragraph that combined the phrase “bittersweet” with a reference to Tabasco AND an allusion to the paradoxical fact that war, as dreadful as it is, can become a catalyst of invention. But I have decided to stop short of writing anything that could be seen as tone-deaf or insensitive and, instead, I will say only that it has given me food for thought. (I’ll see myself out)

Pocket-sized patriotism

When I think back to that night in Chipotle, liberally applying the sauce to my salad, the thing that comes to mind is the bottle’s unique shape and size. I have only seen pocket-sized Tabasco bottles that fit snugly in the palm of one hand. Do they make bigger bottles? If they do I don’t think I’d want to use them. There is something deeply satisfying about the modesty of those little bottles, reminiscent of bottles of aftershave (indeed, McIlhenny based his bottle design on old perfume bottles), imbuing them with a certain artisanal aura, and a sense of scarcity, which together make the sauce inside feel potent and precious.

Another distinctive feature is the bright red hexagonal cap. It is tiny and fiddly like a one-stud LEGO piece, always at risk of being dropped at any moment. Even for the most conscientious among us, unscrewing a Tabasco cap is a special kind of challenge, demanding what is surely—in a world that increasingly favours convenience—an unreasonable level of focus and dexterity. Screwing the cap back on afterwards is even more precarious!

But it’s this unique combination of non-condescendiness, glass-sturdiness, hand-holdiness, and pocket-snugliness that makes the Tabasco bottle such a coveted item. Especially, it turns out, among military personnel.

During World Wars I and II, U.S. soldiers were having to sustain themselves on the battlefield with nutritionally adequate (by the standards of the day) but soul-suckingly dull and monotonous rations of beef, bread, and beans served cold in cans. The widespread need of soldiers to flavourise their lunch—together with the favourable fact that Edmund’s grandson and future president of the McIlhenny Company, Walter S. McIlhenny, served in both wars, earned the Navy Cross AND the Silver Star, and even created the “Charlie Ration Cookbook Kit” (a cookbook wrapped around a Tabasco bottle)—helped to cement Tabasco Sauce among military folk as the go-to way to “fix your food.”

The brand’s identity became closely tied to ruggedness, hunting, patriotism, and blowing shit up, which, as you can imagine, resonated deeply with service members and relatives back home, creating an unstoppably effective narrative any marketing executive would die for.

And when in 2011 the U.S. Army switched the glass bottles for ketchup-style sachets in an attempt to reduce costs, they were eventually forced to ditch the sachets and bring back the beloved bottles, so concerned were they that ignoring the soldiers’ fervent demands could create a genuinely consequential dip in morale. Viva la re-zest-ance!

If you put an OG bottle of Tabasco from the early 1870s (as you do) beside one from your local supermarket today, you’ll see that the only significant graphic change has been to re-orient the wording on the diamond label by about 45 degrees.

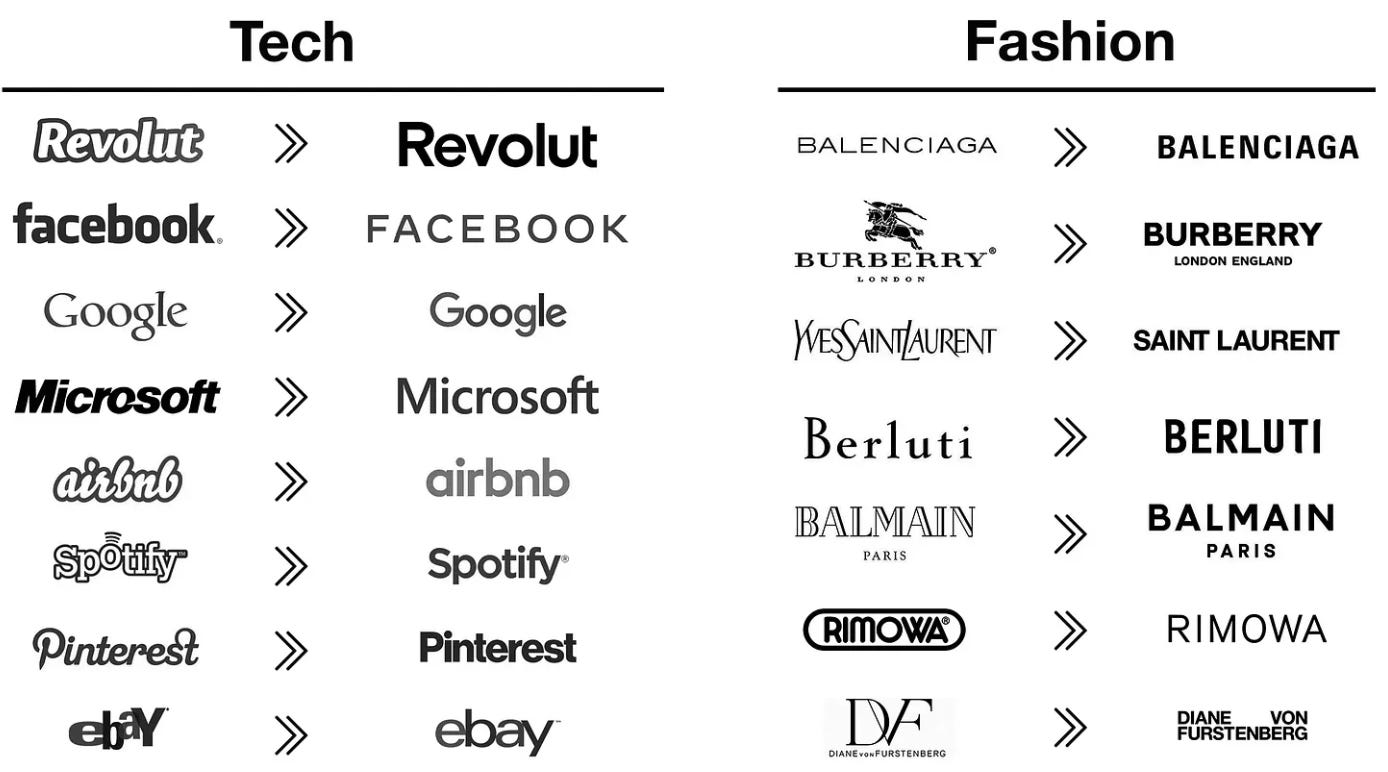

In 150+ years, the visual voice of Tabasco has remained warm and homespun. That is, compared with an overwhelming proportion of other brands—both inside and outside the food industry—that have followed the same prevailing trend towards a colder, minimalist aesthetic.

The qualities of restraint and constancy in Tabasco’s visual identity have gone hand-in-hand with those same qualities born in the production side of the sauce that, together, have helped Tabasco age very well indeed. I’m not talking about the fact it’s aged in oak barrels for three years; I’m talking about how it has survived thrived in the broader social context of increasing consumer skepticism about ultra-processed foods.

Whether it’s gluten, carbs, calories, high levels of salt and sugar, artificial colours, or long discordant lists of chemical preservatives that you’ve taken a stand against, Tabasco Sauce emerges as pure and blemish-free as those polished bottles in Chipotle. The original red sauce (Tabasco’s flagship product) is dauntingly simple with just three ingredients: tabasco peppers, vinegar, and salt. And the amount of salt is on the order of tens of milligrams per teaspoon, way less than a comparable dose of ketchup, soy sauce, or stock.

In a marketplace full of food accompaniments bloated with thickeners, gums, stabilisers, sweeteners, and lord knows what else, Tabasco Sauce looks less like a condiment and more like a cleanse.

The cult of the little bottle

If you thought McIlhenny’s little bottles had reached their extraordinary status just by looking good and sitting on tables in popular restaurants, then you have vastly underestimated the lengths human beings will go to to ensure they are never more than an arm’s length away from it.

There are people (ordinary people, not brand ambassadors or marketing executives) who carry Tabasco in their handbags and ni their glove compartments. This practice has become so widespread that you can now buy officially licensed Tabasco keyrings that hold a real 1/8 oz glass bottle. A South African seller markets these as “the hottest keyrings” money can buy.

Elsewhere, British singer Rita Ora did a radio interview in 2012 where she confirmed she “cannot taste” food anymore without adding Tabasco. And, apparently, she is crazy about—I shit you not—banana-and-Tabasco sandwiches! Or consider the fans of the TV show Roswell, in which the alien teenagers are foreever drenching their food in the stuff. When the WB Network threatened cancellation, fans mailed them thousands of Tabasco bottles as a protest campaign.

But pop stars are amateurs compared to astronauts. It turns out that when people go to space, their body fluids flow upwards into their heads, leaving them feeling permanently congested. This means that in orbit, your sense of smell mostly disappears, taking most of your sense of taste with it too. Astronauts on the International Space Station therefore crave sharp, pungent flavours to punch through the sensory fog…a perfect job, of course, for the little red bottle. NASA reports that it is now a staple on all shuttle menus.

The astronauts, the soldiers, the pop stars, the alien-obsessives, and the handbag devotees are all variations on the same phenomenon. Tabasco has become more than just a condiment. It’s a kind of cultural fetish, a way of carrying a piece of home, an expression of aspirational values, a reassurance that no matter how far you drift—whether into space, into a combat zone, or into a neglected motorway service station—you can still give your sub-par food a lip-smacking kick.

And if all this sounds like I’m overstating the case, consider that upwards of 150,000 visitors a year make the pilgrimage to Avery Island, the salty garden where Edmund McIlhenny first started sowing pepper seeds. You can tour the factory, tend the seedlings, walk through the barrel warehouses, and receive your complimentary mini bottle as an edible souvenir.

Of course, there are scores of other hot sauce companies getting in on the action now. The ones I’ve tried are perfectly decent. But, when you see names like “Da Bomb” and “Ass Reaper” and whatever else is being concocted to make you feel like you’re participating in some kind of gastronomic daredevil stunt, Tabasco Sauce just sits there, quietly content. It doesn’t need to shout.

🌶️

Hey, it’s Harrison 👋 Thanks for reading my publication about creativity as a tool for personal growth.

If you’re ready to make a major career shift through a creative project, I offer professional 1:1 coaching—using principles of Positive Psychology—to help you navigate that transformation.

If you’re interested in exploring what you could achieve by partnering with me, you can send me an email and we’ll set up a call to chat.

Related post

Entertaining and also inspiring in that you were able to take a very small thing - a Tabasco bottle in a Chipotle - and turn it into a good essay.

Super interesting! When I was at Avery Island a few years back one story I heard was that Tabasco spread globally by sending salespeople on advance trips to countries and having them eat the local foods and sauces. Once they had a good handle on things they were able to suggest how Tabasco could be used in a culturally resonant way, and that’s part of how they became the most widely used condiment in the world….