Learning how to learn

Is it better to “be told” or to “find out”?

How are we going to help to educate our hypothetical children? That's the question at the heart of my thinking recently (I’m getting married on Saturday and we’re going to try for kids soon).

I'm hoping that writing will be a good vehicle for enabling conversation with my wife (and with anybody else who’s interested!); good because it will make us think more clearly and rigorously than we could in a verbal back-and-forth. It will also give me and my wife (and our future kids) a record of our research and decision making.

Until just a few weeks ago, I’d never read a book about education. Nor had any conversations about it, nor listened to any podcasts or debates about it (except for the time I sat in the UK’s Houses of Parliament and watched them debate university tuition fee rises in 2011, but that was just a coincidence; I was there as a recently arrived Londoner more interested in the architecture and furnishing my Instagram feed).

They say that the greater the island of knowledge grows, so too does the shoreline of the unknown. And when it comes to education—such a chasm of a topic—I have not even glimpsed the shoreline yet. I’m still in the deep cave at the centre of the island.

The one book I have read so far (Education: A Very Short Introduction) was so rich with facts and insights that I've chosen to read it again. This time, I'm making notes. And it's these notes that I'm using to write to you here.

Without a doubt, the big thesis of the book is that schools have been getting a lot wrong.

It's strange for a book like this to have a thesis because it's essentially an historical survey, a bird’s eye sequence of all the most influential people, ideas and events that have come to shape education. The book has been written by a guy who seems to have had an involved and diverse set of experiences in education—as a parent, a teacher, a school governor, a developmental psychologist, and a school pupil himself, of course. And it’s been published by the very credible Oxford University Press. So, this book shouldn't be laced with opinions or agendas. It isn’t. And yet, school failure is the overall vibe that emerges when you read it; not so much through the author's views (he does pepper-in some of his views) but through the stories he tells of the history of education design and the development of our understanding of how brains learn best.

The big debate

The big debate amongst educators, that stretches back two millennia and still continues today, comes down to whether education should be about instruction or induction. Should we tell young minds what to think or should we teach them how to think? Do we learn things more effectively through structure and discipline or through freedom and play? Is knowledge best delivered or discovered? Is our goal to preserve society or to transform it? Are the abilities to do all of this best cultivated from without or from within? Should curriculums be subject-focused or child-focused?

These are massive questions. And, to be honest, I feel surprised that we're even being asked to choose! Surely we'd want the best of both worlds, no? What's with all the tribalism?

But the fact that parents, educators, politicians and students themselves are still divided over this, and have been since at least ancient times, is a strong signal that there must be more to it than meets the eye—and that it isn't the sort of thing that can just be trivialised or waved away.

Broadly speaking, those who believe that education (which the author defines as “sharing ideas and passing down skills and knowledge”) is about transmitting knowledge from teacher to child can be thought of as belonging to the formalist school, whilst those who believe education is about the cultivation of knowledge within the child belong to the progressive school.

Some of the arguments each school puts forward include the following:

Formalists

The formalists say there is important knowledge that people must have in order that they're not ignorant and thereby cursed to repeat mistakes made by others in the past (think wars, slavery, corruption, tyranny and all of the world's many isms) and, also, in order that they can build on the wisdom and achievements laid down by those who lived before them (think medicine, the arts and sciences, maths, pretty much everything that surrounds us).

This, formalists say, is knowledge that you can't just “discover” when left to your own devices. It has to be collected, organised and taught to you so that you have a well-rounded understanding.

The formalists even go so far as to say that to let children struggle to figure things out on their own, and to waste time and energy when there may just be some knowledge they need (which you could teach them), is not only unnecessary, it borders on sadism.

The essential argument of the formalists is that if there were no formal processes to administrate learning, then we'd each end up acquiring our own specific knowledge but there would be far less shared understanding, and a lot of invaluable information would be lost or overlooked.

We would all become those proverbial children, ignorant of everything that happened before us.

Progressives

If you asked a progressive, they would say that whilst they agree children should be aware of historical information, you don't foster that awareness by forcing kids to learn under compulsion. We learn best when we are emotionally invested, when we can raise our own awareness and arrive at the insights ourselves.

We do not need to be taught how to walk or talk, do we? Learning happens naturally and inevitably provided we're given the right conditions. In fact, the progressives plead, if we did try to teach kids how to walk and talk, we'd confuse them and they'd never learn anything.

We should be wary of the mere “transmission” of information; facts are useless without context. What is the point in knowing the names of all of Henry VIII's wives if you don't understand how it affects you today?

Far from being sadistic, allowing children to work things out for themselves fosters resourcefulness, resilience, and self confidence—and turns them into useful members of society.

The essential argument of the progressives is that if there was no freedom for us to pursue our own interests, then we’d have our curiosity, creativity and inventiveness pinched out of us. We’d learn to distrust schools and even learning itself.

And we'd all become those proverbial robots, compliant and inert, ignorant of our full potential.

There's much more to both sides than what I've said here. And if you take any one of those points and view it under a microscope, it's a whole lot more complex.

But this is the general gist, the common battleground humans have been fighting on for more than 2,000 years.

The fundamental and seemingly insoluble question at the heart of education is: what’s better? “being told” or “finding out”?

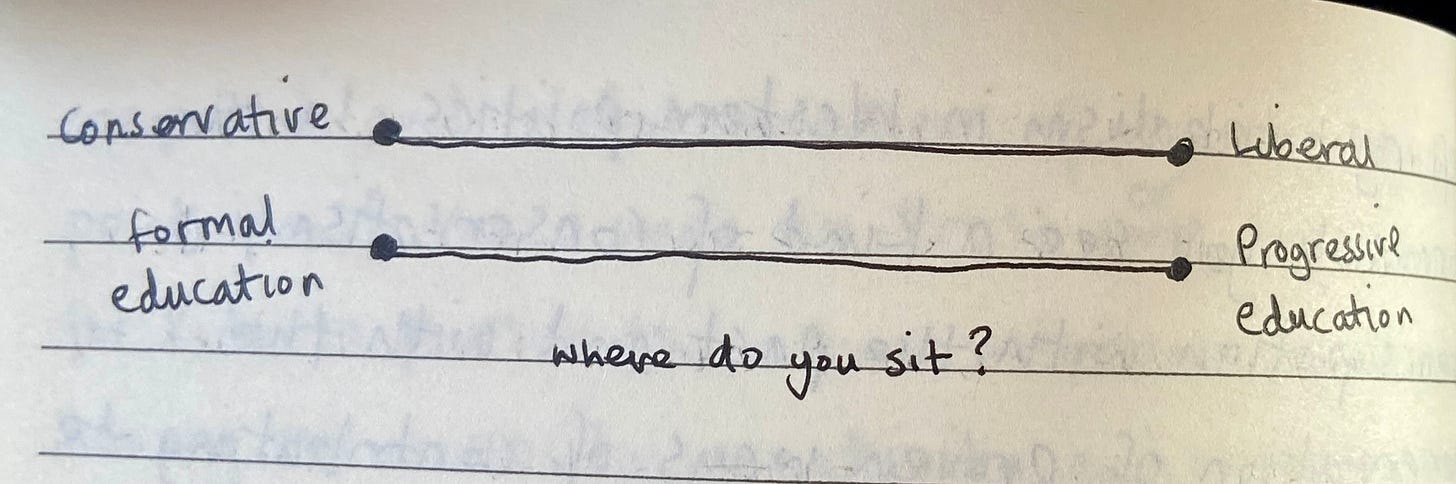

There are some interesting overlaps between this educational conundrum and other spheres of life. You can overlay this tribalist thinking in education fairly neatly onto the left-right tribalism in Western politics.

In the formalists, you see a kind of conservatism, a preoccupation with the past and the preservation of proven ways of contributing to society.

In the progressives, you see a kind of liberalism, a respect for what might be, and a championing of the liberty and questioning mindset needed for innovation and renewal.

If I've been ignorant about education, then I've certainly been ignorant about politics, and my questions are bound to be a bit naive. But I've always wondered why we have such an ingrained standoff between “the left” and “the right.” Other countries, like some of those in Scandinavia, have multiparty politics. And as individuals, we know that black-and-white thinking is rarely, if ever, a wise perspective to take.

So, why is it such a perennial feature of our thinking in politics and education? It's almost as if there's something intrinsic to the human psyche—something biological, even—that casts our experience of the world as spectrums with poles at either end.

To be fair, this isn't a new idea. There's a strand of psychology called Polarity Management that deals with these kinds of dilemmas. Life is full of them. Like two sides of the same coin, each defines the other: hot-cold, up-down, certainty-uncertainty, explore-exploit, individualism-collectivism, freedom and constraints, etc etc.

The wisdom of polarity management is just that: management. These are dilemmas that can't be “solved” once-and-for-all; they need to be managed our whole life through. In other words, it's not about adopting one side at the expense of the other; it's about combining the two.

Importantly, it's not about having equal measures of both poles at the same time and trying to squat in the middle of the spectrum. If you think about it, the fact that we've only got so much time, so much energy, so much focus in a given moment, means we have to commit it somewhere. We have to place value on something, at least for a time. And, by definition, committing to one thing means not committing to other things. Indeed, commitment itself has its own polarities.

We can't have equal measures of commitment and non-commitment. But what we can do is commit for a while and then relax that commitment later.

We can't be equally free and constrained at exactly the same time. But we can be free one moment and constrained the next.

So, when it comes to life's great polarities, instead of sticking doggedly to one pole, or trying to root ourselves to the dead centre of a spectrum, we must try to move along it from left to right and back again. We must spend some time choosing one thing and then choosing its opposite.

This dynamism, this flowing between poles and tasting the best of both sides, is a much more accommodating view of how human beings thrive. Not only does it get us out of tribalist thinking, it presents us in our most diverse, creative, conflicted and colourful image.

And it can release us from having to believe certain problems need solving at all. There are many thorny challenges and confusing questions in life, but how many of them are just polarities masquerading as problems?

I suspect that left-right politics is one of them.

And I suspect that progressive-formalist education is one too.

The question, then, is how to give the best of both worlds to our kids. Which formalist ideas, and which progressive ideas, should we commit to? And when?

I want to understand this more. My instinct is to start researching at the very beginning, with our earliest major learning milestones—walking and talking. This might lay down some foundational understanding about young minds and bodies in the process of learning.

At the very least, it could give us some principles, insights or clues that we can take with us as we learn more.

In the spirit of learning to walk before we can run, and since walking typically comes before talking, I think walking is a good place to start. And that's where I'll pick up again in my next post about education.

If any of you reading this have ideas, experiences, stories, data, questions or suggestions, and you’re up for starting a conversation about this, I’d love to talk, so please use the comments section below and/or email me.

Thanks for supporting The New Workday, and I’ll see you next time.

Harrison x

⬥

Want to read some more? My writing’s grouped by:

And you can read how this blog can help you here →

Great article Harrison. I love how you’ve approached the debate and that you’re thinking ahead.

I am interested to learn more about polarity - as I am often accused of sitting on the fence! Maybe knowing it exists will help explain myself.

When I was at school I thought I loved it. I’d been bullied and was traumatised but kept telling myself it was all part of education. What I actually loved was learning! That burst of confidence in overcoming a maths problem or remembering a moment from history that I had the opportunity to share. Getting praise for an art project or a piece of writing gave me pride in what I could achieve.

My twins are 16 and have given me a unique perspective on education as they’ve grown up.

My daughter has recently finished her GCSE exams and will get the results this coming week. She shines with the arts - often getting praise & encouragement from teachers on writing, art and music (we will see if it translates into actual grades!). Maths was a different story with an online homework app that you must get 100% correct and the ‘lessons’ where she was regularly berated by the teacher as if it was her fault when she (& her friends) didn’t understand something.

My son enjoyed every subject including maths, regularly shouting out the answer if we ever had a quiz and getting praise for his writing. Unfortunately he was bullied all his school life to the point where he felt unable to return in year 7 (first year of secondary). It coincided with the lockdown which meant we could see that there was another way. After a lot of battling with the authority and under threat of prosecution, we deregistered him to take on his education ourselves. Naively I made an attempt at ‘structure’ & teaching him. Didn’t work. I realise now and the word used in Home Education circles is that he needed to ‘unschool’ - effectively recover. Now he feels ready to go back to education but this time at college. Where he gets to choose to attend and choose the classes he’s interested in. Smaller class sizes means he’ll be seen as an individual and have much more support than school could ever offer.

Over the last few years I became anti-school. I saw the struggle of both my children and hated the system. As a tutor it became clearer that our education system just doesn’t suit everyone and yet we’re forced down that route - effectively punishing parents when their kids didn’t fit into it.

Coming out the other side where my children can leave school behind, I feel relieved. Relieved that we survived. I firmly believe that they can and will thrive now.

Sorry for the long post, I hope it helps with your research.

Great article, and I’ll come back to give it a re-read in a day or two. Two points popped up as I was reading, so I thought I’d share while they were fresh in my mind. The first was about how we’d likely confuse infants by explicitly teaching them to walk and talk. Yes, but children don’t exactly learn these things on their own. They see/hear them modeled, and generally in very loving and supportive ways. Getting baby to walk to daddy generally involves a lot of repetition, encouragement, eye contact, and a reward (cuddles, hugs). Children left alone or neglected are delayed in many ways, and in extreme abusive situations don’t even acquire a first language. Walking and talking don’t happen spontaneously.

The second thing I wanted to mention is that keep in mind that crawling comes before walking. I think it’s the first independent movement. I don’t know if that actually ought to change your focus, but it wouldn’t hurt to keep that in mind.

A million good wishes to you. Again, great article.