Hi Friends 👋

What’s the hardest thing you’ve ever chosen to do?

And what did it teach you?

We have a hunch you don’t regret a second of it.

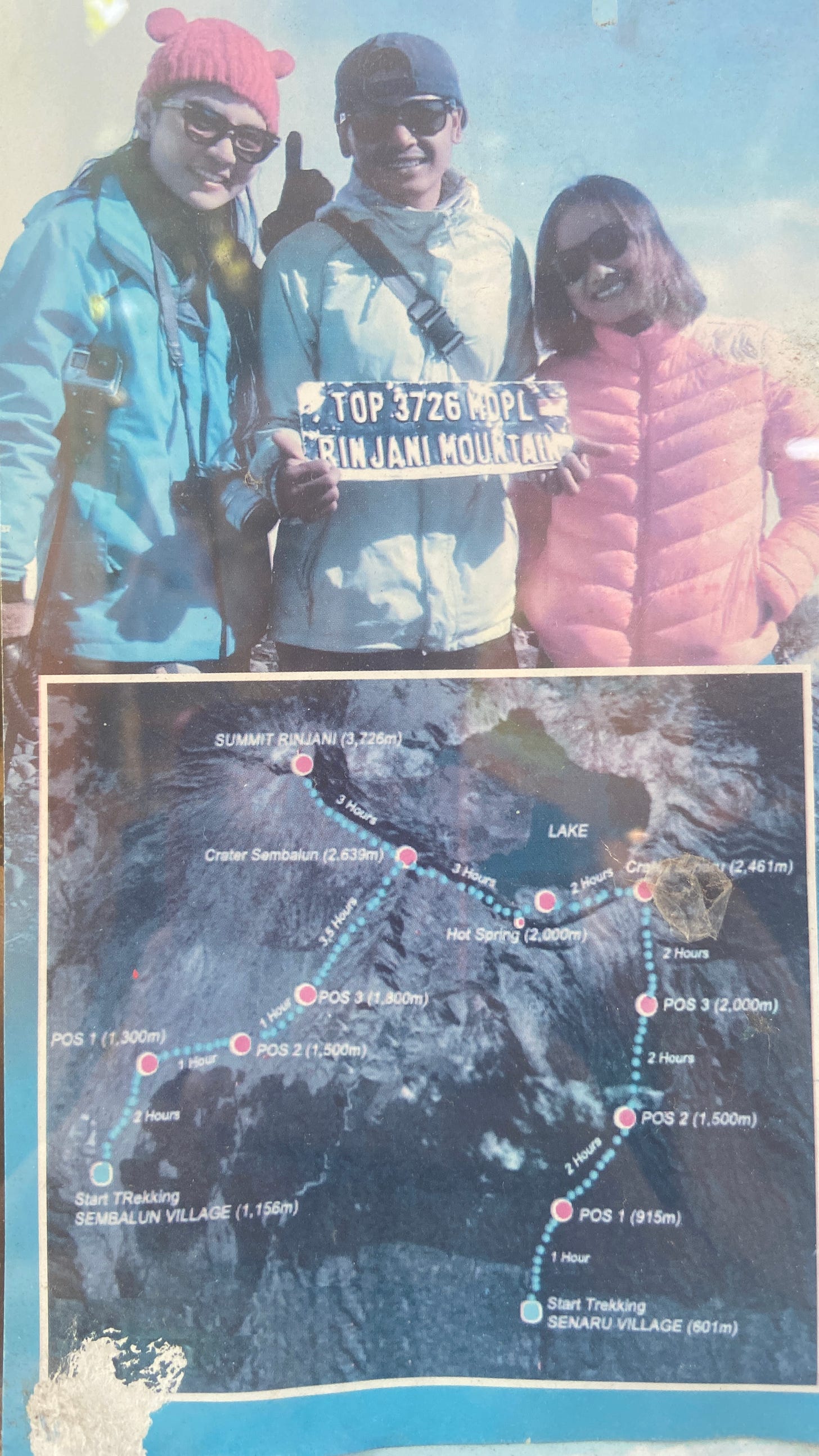

We just trekked up Indonesia’s second highest volcano: Mount Rinjani, in Lombok. We had no preconceived notions about the trek save for a few benign, sun-bleached images of smiling trekkers printed on the many rubbery hoardings seen around town.

The real Rinjani is unspeakably more dazzling than those images. The 66 million-year-old landscape begins with dense jungle that eventually gives way to treeless, grass-covered nobbly hills. Later, as the mountain starts its interminable ascent, it morphs into pine forest, continuing all the way up through the canopy of clouds, clouds that are there one minute and gone the next, yet never appear to move when you watch them.

Rising still above the clouds, where it’s so high not even the birds dare to venture, Rinjani’s 3726-metre summit thrusts into the heavens, its vaulting peak marbled with solidified molten lava – a chilling reminder of its destructive potential.

And to reward you for all your dedicated climbing, your unrivalled view from basecamp is looking down on the secret lake at the bottom of the crater, a lake the size of New York’s Central Park, as deep as two Statue of Libertys, and as silent and still as a held breath.

In Europe when you can only see a thin sliver of the moon, it's usually of the left or right hand side of it. But here in Indonesia you can see the moon’s underbelly. It looks like a little smile, proud of the countless stars it shares the sky with.

In the darkness of night, it’s not possible to see the ocean, but you can see all the fishing boats anchored, whose twinkling lights are indistinguishable from the stars, creating the illusion that you are no longer standing on earth, but floating in space.

Our decision to “do Rinjani” was made on pure whim, while channelling our “just say yes, worry about how later” travel vibes. We’d done nothing more than a quick Googling to find out that you could choose a one-day, two-day or three-day trek. Emboldened by our new work-less-play-more approach to life, and anaesthetised by our own naivety, we went for the three-dayer, of course. How hard could it be?

Turns out it was hideously hard. The hardest thing we have ever done by a country mile. So hard, in fact, that it made us expose parts of ourselves we’d have preferred to have kept buried – different demonstrations of extreme desperation.

Our fate was foreshadowed during a brief exchange on the boat over to Lombok, when a woman asked us whether we were doing one, two or three days, and grimaced when we said, “three.”

But Rinjani also humbled us, helped us reach more acceptance with who we are, and brought us closer together by making us respect each other even more. Not that we didn’t believe we could count on each other before Rinjani, but after what we went through getting up there, and back down again, we now have an even deeper sense of certainty that we can come through anything together.

We’re writing this essay from the beach of our adopted home of Gili Air (a tiny, idyllic Indonesian island) having just returned from the Rinjani trek a day early! We were so overwhelmed with fatigue and pain and despair up there that we chose to cancel proceedings 36 hours prematurely, and then endure an unprecedented, hair-raising schlep home, which involved parting ways with our trekking group in the belly of a 1000m ravine, clambering back up to basecamp, following a porter called Arwal down a treacherous 4km descent in the pitch black, and paying locals to take us across another 4 kilometres of gnarly terrain on the back of their rusty, rasping crosser bikes in the dead of night. It took 22 hours for us to get home.

We were no match for the cruel inclines of Mount Rinjani, for the slippery volcanic scree that swallowed our feet, filled our socks with blistering gravel, and mocked our every step. It constantly lured us into the false belief that we were finally being treated to some flat ground for a while (huge deep breath), and then, just as we began to wonder whether the worst was now behind us, bang!, it threw another sheer rock face at us, each one more brutal than the last, while the summit only seemed to get further and further away.

We were no match for mountaineering generally. Not at those altitudes, anyway. But we tried it. And we reached our limits. And that’s a win on both counts.

In a poignant twist of irony, which only revealed itself in the fullness of time, Rinjani humbled us again by reminding us that it’s too easy to judge people wrongly. When we first set out on the morning of day 1 (we’re talking about the most reasonable part of the trek here, the bit that takes place through nobbly fields) the noise and stench of crosser bikes weaving in and out of the trees around us got on our nerves because we assumed it was local misfits, attracted by the spectacle of tourists, showing off and being a nuisance. There was something about the bikers that felt antisocial. There we were, trying to enjoy the mountain and the beauty and the silence and the fresh air, and here were these idiots on smelly, polluting, ear-piercing bikes totally ruining the moment.

But little did we know, we could not have been more wrong about them. We came to learn that they were not local misfits at all, but kind people who were a vital part of the infrastructure helping the entire mountaineering operation to run smoothly, transporting materials and people in need (people just like us) across vast distances, saving them from having to walk when they are injured or collapsed.

In our hour of greatest need — after we’d spent eight hours reaching Rinjani’s basecamp, then woken at 2am to walk another seven hours to and from its summit (encountering uncontrollable tears at the top), then another seven hours dragging ourselves down and back up the 1000m ravine, and, finally, another three hours wincing and wailing our way back down to sea level in the black of night through unnavigable jungle, with the ominous battlecry of unseen creatures closing in all around us — we became utterly dependent on these “misfits” for our survival and safe return home.

The bikers brought us out of the darkness, took us to an ATM, organised a taxi to take us to a hotel, and they even helped our porter Arwal get home too. Words can’t describe what their calmness and generosity meant to us in that moment. And to think: if we hadn’t needed their help, if we hadn’t encountered them again after that first leg, we’d have gone on with our lives in total ignorance, bitching about them to anyone who asked us about Mount Rinjani.

We have been truly humbled by Mount Rinjani. The physical punishment, the mental torture, the unassailable challenge of that mountain, that massive looming mountain, which has claimed dozens of lives and injured hundreds more, sent us back down to earth like squatted flies. And being forced to see that we had judged people unfairly, people who ultimately became our saviours and showed us unwavering, indiscriminate care – that was humbling too.

But perhaps the deepest lesson in humility was one of self-understanding and self-acceptance. We’d always thought of ourselves as intrepid travellers, favouring the world’s rougher edges, thriving without comforts. Rinjani taught us that as much as we like to see ourselves as modern day explorers ready for anything, the reality is less exciting. There’s a certain size and shape to our adventurousness, and it doesn’t include climbing volcanoes.

It’s disappointing for us in one sense because it’s hard accepting our limitations, especially when so many people younger and older than us were up there doing it without a grumble. But at the same time it’s really nice to register another notch of self-awareness, shed some of the pressure to be good at everything, and feel ourselves integrating, rather than resisting or denying, ourselves.

As well as the profound “everything you need is on the other side of hard” rewards that the Rinjani ordeal gave us, it also provided a shining example of a mysterious truth: that if you voluntarily choose the harder path over the easier one, it tends to be the right choice, and you end up gaining much more than you lose.

When we’d given up, our plan was to stay one more night at basecamp and then get the hell off the mountain first thing in the morning. Our head guide, Sun, ok’d this plan and arranged for Arwal, one of the porters, to accompany us back to camp. Porters support trekkers throughout their journey on the mountain, carrying tents, sleeping bags and cooking equipment – 30kg of gear you need to survive on the mountain in 0 degrees — all stuffed into reed baskets balanced on a bamboo pole, which they rest uncushioned on their shoulders as they traverse the lethal landscape in mere flip flops. Arwal was assigned to shelter and feed us at basecamp.

It took me and Corina three hours to climb back up to camp while Arwal shot ahead to prepare the tent for our arrival. If you’re wondering how a porter carrying heavy equipment could “shoot ahead” of us, it’s because firstly, we were completely shattered by that point, and secondly, porters are adapted to that environment and able to ascend and descend the mountain faster than trekkers.

However, on our way up, me and Corina did some maths and realised there was still enough time left in the day for us to get to camp and walk off the mountain that afternoon, and that we could be safe and sound in a hotel that evening, with hot showers and a real bed, ready to sail back to Gili Air the following morning.

This prospect was so intoxicating that it gave us a renewed burst of energy, and we pushed and pleaded with our bodies to get us to camp as quickly as they could. We made a plan for our arrival and immediate departure: I would let Arwal know we were leaving, while Corina would find more water for the journey.

But when we got to camp, we couldn’t find Arwal. There were hundreds of tents and hundreds of trekkers, porters and guides swarming about. Basecamp itself was split into six zones spread over the crater rim. We could have spent an hour searching for Arwal and still not have found him.

We didn’t have time to spare. We were running out of daylight. We felt pretty confident we could retrace our route off the mountain and we wanted to avoid doing it in the dark at all costs, so we resolved to leave immediately, and asked one of Arwal’s colleagues to pass on a message that “we were very thankful for all his help, and we’d decided to go home tonight instead of tomorrow.”

But his colleague said we ought to discuss it with Arwal first. That’s all he said. And he didn’t say why. But it was enough to suggest we’d be making a mistake by leaving without doing so.

We were absolutely out of our minds, hyperventilating, marching up and down the campsites shouting Arwal’s name. But nobody knew where he was.

Even though the mountain had demoralised us, even though we’d agreed to leave and not let anything or anyone stop us, even though we had nothing left in the tank and the easier of the two choices was just to leave, the better parts of ourselves chose to wait to speak to Arwal.

In the final reckoning, it turned out that if we’d left without him, Arwal would have become stranded, unable to get home the next day. This is because he was due to share our transport from the bottom of the mountain to the starting village some 50 miles away, which was the village where he lived. In other words, Arwal had been assigned to us precisely because he lived in the same village we were returning to, and we were his ride home. But we didn’t know any of that at the time.

Sentencing poor Arwal to abandonment was the first travesty we avoided by choosing the right-hardest choice. And the second travesty is now so obvious with hindsight that it’s barely worth saying: without Arwal to lead us off the mountain in the first place, and be our encouragement when we thought we couldn’t continue, me and Corina would have ended up in the middle of the Indonesian wilderness, in pitch black, with nothing to orient us or connect us with the outside world (we didn’t have local sim cards in our phones), nothing to shelter us, nothing to eat or drink, only the terror of being alone and lost, in freezing temperatures. It doesn’t bare thinking about.

Despite how abhorrently hard trekking up and down Rinjani was, especially when it went dark, we always had Arwal’s head torch just a few metres ahead of us – our north star – a glowing link in the unbroken chain of cooperation and kindness that led us all the way home.

The experience overall was so rewarding in its own fucked up way that we’re as convinced as ever there’s great value in meeting certain challenges without knowing too much upfront. It’s too easy to limit yourself when you have prior knowledge or experience. So many great achievements are achieved by naive people who don’t know how hard something is before they begin.

Then again, to choose the peak of a mountain without considering what it’ll actually be like to climb it is pretty dumb. The struggle is worth it. But know your mountain!

See you next time!

– Harrison & Corina

Don't keep this mountain of insight all to yourself. Spread the wisdom, amplify the climb!

💡 After a year of working travel, we captured 99 lessons that gave us an edge →

Wow what a journey. It sounds challenging, enlightening and inspiring. God luck both of you in your next adventure

Fantastic, epic story, Harrison and Corina, very well told. An odyssey in itself. Well done for making the right decisions at those critical junctures. Looking forward to hearing it all again, first hand.