What your favourite artwork says about you

Knowing which art you like, and why, helps your creative practice to flourish

Hey folks

How can looking at art help you develop your creative practice?

I arrived at this question after learning some useful things about myself by thinking deeply about a particular artwork that I love. It’s my favourite artwork in the world.

What I'd like to do in this post is offer you a way of doing the same—of turning something you like into something that helps you create.

Maybe you'll be able to find more of the stuff you like. Maybe you'll become an even more interesting person. Maybe you'll feel more comfortable in your own skin. After all, having a better understanding of yourself and your practice will have all kinds of exponential benefits. Remember what the Oracle said to Neo in The Matrix: “Temet Nosce”

This favourite artwork of mine, it’s one of those things that I've liked for so long now and brought up in so many conversations that eventually—and this happened recently—I blurted out, "But WHY do I like it so much?!" I blurted it in the tone of a rhetorical question, except this time, it wasn't rhetorical. And I decided to try and answer it.

Before we dive in, I want to say a few words about the power of the question “why.” What do you think about when you think about the question "why"?

Maybe you think of the paradigmatic kid in the front row questioning the teacher, or the teenager in the backseat of the car whilst mum sits upfront looking all pestered, "That's just how it is, sweetie!" "Yeah, but why?"

Maybe you think of Tim Urban's extremely popular blog Wait But Why.

Perhaps you're a fan of Simon Sinek's work and his book Start with Why.

Or, if you work in product management or a related field, maybe you think of the Five Whys technique used so successfully for uncovering people's truest motivations.

Personally, I think of all of these things.

And I also think about the times I got something significant done precisely because I provided a "why" along with my request. For example, when I was ordering new specs that I wanted fast-tracking, the rep was like, "It takes as long as it takes, I'm afraid," until I added that I wanted them soon so I could wear them to my wedding and the green would match my suit and tie, to which the rep replied, "I'm getting married next month too, congratulations! Okay, I’ll speak to my manager and get them put through for you more quickly."

Have you ever noticed how you can deepen a conversation with anybody, strengthen your connection with them, and learn a fuck ton more about them when you follow up your surface-level questioning with "why?"

And one more thing for the "why" pile—I can't resist mentioning that experiment where a person was able to succeed in pushing into the front of a range of different queues just by providing a "why." The reasons weren't that compelling either, but the "whys" were enough to achieve the improbable. FYI, the experiment was conducted in England where we flippin’ love ourselves a queue, and it is not easy, by any means, to push into queues in England.

What all of these examples illustrate is that "why" is a bloody powerful concept, whether you're asking it or giving it. And so, if you're feeling up to the task, I say it's one of the most illuminating things that you can do for your self-awareness and personal agency—to question why you like something.

And if it's something that you really like, the way that I really like my favourite artwork, then it's worth getting as forensic as possible about it because, why not? You stand to learn a great deal about yourself.

Here we go then. Here is my favourite artwork in the whole wide world.

I'd show you a picture of it, of course, but I can't show you a picture of it because I've never actually seen it. Now, you might think that's the most interesting thing about all of this. But it's not (and I’ll explain why I’ve never seen the artwork at the end of this post). The most interesting things about it are the three reasons I like it.

My favourite artwork

Some clever artist, the instigator, had the idea of commissioning nine other artists to each design one hole of a nine-hole crazy golf course, so that what they ended up with was a fully functioning crazy golf course comprising nine different artistic responses.

When I imagine this artwork, I imagine it bursting with colour.

I imagine each hole speaking its own language, surprising me with its own ingenuity.

I imagine some of the holes devoted completely to fun, while others alluding to famous people or famous events, or to certain fashions or period styles.

I imagine encountering each hole as a golf enthusiast, or as a husband or father playing a round with my kids—placing my ball on the tee and then walking around it, puzzling, figuring out which routes to take and which to avoid, admiring the clever quirks and focal points that each artist has added.

I imagine having a favourite hole amongst the nine. It wouldn’t be the hole that I got the best score on. It wouldn’t be the hole that looked the nicest. It would be the hole that most pushed the limits of what a crazy golf hole can be—perhaps not looking anything like a hole of crazy golf at all, but like something else completely, like a metaphor of a golf hole.

My favourite hole would be the hole that surprised me the most, that challenged me the most, that showed the artist enjoyed themselves the most. My favourite hole would be the one rigged with pranks, the one that everyone remembered afterwards for being a bit “weird,” the one that swallowed someone's ball and didn’t give it them back.

I love love love this crazy golf artwork so god damn much that I'm excited just thinking about it right now. It is everything—everything—that I want in an artwork and an idea.

Let’s get more specific now. Having thought about it lots, there are three key reasons why I love the crazy golf artwork. I love it for its:

useful uselessness

sweet spot of constraints, and

blend of individualism and collectivism

I'm going to do a little deep dive into each one of these qualities, and hopefully I can figure out what it says about me, how it helps my practice, and how you can do the same by exploring why you like what you like.

1) Usefully useless

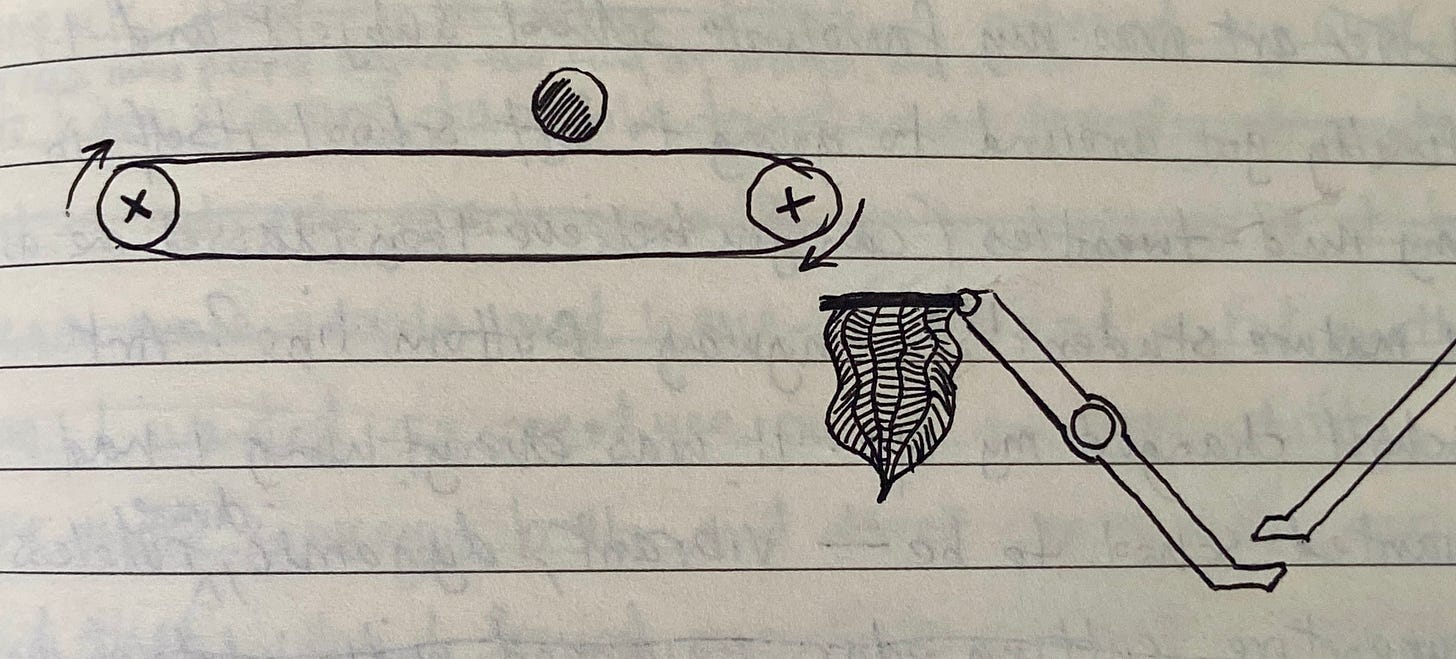

When I was a kid, between ages five and ten, I remember making drawings for my dad. The drawings were on A4 paper and were side profiles of large, multi-occupancy vehicles like tanks and ships. In different parts of the vehicle, there were little scenes involving stickmen pulling levers or hoisting cargo or doing other questionable things. Connecting these scenes were all manner of contraptions, with conveyor belts, cogs, buttons and knobs. The thing that captivated me so much about drawing all of this was figuring out how one component in the system triggered the next, and then trying to draw this as faithfully as possible.

Unfortunately, those childhood drawings are lost forever, and I can't show you any of them. But here is what they would have looked like—a rough approximation.

Looking back now, I can see that my young brain was finding ways to think visually about logic and cause and effect (if this happens, then that happens). And even though the contraptions I drew were wacky and pretty useless on the face of it, it was very important to me—vital even—that the contraptions did what they were designed to do. This, incidentally, is what I like about the crazy golf artwork. Wackiness and uselessness are in the very DNA of the idea (the clue is in the name), but it still has to function properly. People still need to be able to walk around it, and the ball still needs to go in the hole.

What does this say about me? I think it goes a long way to explaining why I ultimately chose to stop being a professional artist and become a writer instead. This was very unexpected. Art was my favourite subject at school, and it changed my life completely. Art school was everything I had wanted education to be—vibrant, dynamic, diverse, and rule-breaking. I made so many new friends, grew so much more confident and imaginative. I exhibited work in over 20 international exhibitions. I even met my wife at art school. I thrived so much as an artist that I made my bachelor's last for four years instead of three, and then went straight into a master’s that was two years instead of one. It's hard for me to overstate the transformative impact art-making had on my life—nothing short of giving me a proud new identity.

And yet I grew out of it because I began to realise that no matter how good I could get at making art, no matter how much I relished building things with my hands, as long as it was just art, it was only ever going to have a minuscule impact. I wanted the work I did to reach far more people beyond the tiny, incestuous art world, and I wanted it to have some form of utility too, like those conveyor belts and that crazy golf course.

That's why I eventually found myself drawn to nonfiction writing, which is a much more accommodating vehicle for my creative needs. Nonfiction gives me infinite scope for wackiness and creativity, but it demands that what I write is useful, or at least interesting, to others.

There was an influential art style and movement back in the early 2010s called Arte Útil, which, when translated, means "useful art." It was spearheaded by the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera and her followers. And essentially, they believed that art should have a use to society beyond just being aesthetically pleasing.

Fans of Arte Útil wanted art to have some kind of social, political or environmental impact. As a result, their artworks were often collaborative, inclusive and egalitarian. They often didn't even look like art but more like events or activism. And they certainly weren’t concerned with material objects or the machinations of the art market.

With my left-leaning social sympathies, I too want art-making to break out of the ivory towers and stuffy world of academia and to be accessible and enjoyed by everybody. I want art to meet people where they are.

But I wouldn't go quite as far as Bruguera. I still buy into the notion of art as a non-useful entity. I want art to retain some of its uselessness because I think there's a lot of freedom and power in that for people—freedom from the obsession with measuring and instrumentalising everything, and freedom from every single thing having to be productised and sold before it's deemed worthy or valuable.

There’s power in useless art, too, when it allows the creator and the consumer to reclaim time for themselves and engage in a way that isn’t linked to making a living or putting food on the table. Obviously, we are more than just our abilities, skills and productivity. And choosing to spend some time enjoying artefacts that don’t serve a clear purpose can be a very strong social and political position to choose, especially in a world that rewards us readily and lavishly for our consumerism, obedience and conformity.

The crazy golf artwork shines so brightly for me precisely because it meets these varied yet somewhat conflicting needs. It manages to be useless and yet also useful. And it manages to be elevated and yet remain accessible. It straddles the boundaries of art and design. And it brings together highbrow and lowbrow culture really nicely.

Art shouldn’t be divorced from everyday life. I agree. It shouldn’t be inaccessible, aloof or disinterested. To make art purely for art’s sake and create things that are purely aesthetic can come across as indulgent, entitled, and even arrogant to people who don’t have the luxury or even the basic resources needed to make art in that way.

At the same time, I sympathise with those who defend art’s special arena where we get to spend time and resources on projects just because we like them—not because they make any money or even make any sense. Art might be the only place left on earth where we get to make choices and try out things that aren’t functional, that don’t need to “add up,” that don’t need to be measured, packaged, sold, or bought. It’s a place where we can have fun, be curious, daydream, take risks, and opt out of the rat race. And that’s an important idea and an important privilege too. So, I also feel we should protect the artist's ability to be functionally useless if that's what they choose to do.

The crazy golf piece captures those two ideas perfectly. It is a rare combination of unselfconscious creativity and down-to-earth utility, and it’s the first big reason why I love it so much.

As for how it can help me, I suppose it’s a clue to the type of art that I should be seeking out, the type of work I should be involved in, and the sorts of people I should be knocking around with. I want to hang out with people and projects who take something conventional and then renew it or reinvent it. I want people and projects that happily blur the boundaries of disciplines and ideas.

How can all this help you? What could I write that could equip you with some questions and answers that you could use in your own quest for creative enjoyment and personal fulfilment?

I would say, think about your favourite artwork, the one you’ve mentioned a lot. If you think you don’t know enough about art to have a favourite, then you could spend time on things like this TV series, this lecture series, or just go and spend a day in the bookshop of a major gallery or museum in your town and talk to the people who work there. Once you’ve seen a bunch of art and one piece in particular resonates with you, think about why you like it. Ask many questions of it. Is it something about:

the way it looks?

the materials it’s made from?

who made it?

why they made it?

what it reminds you of?

what it represents?

On this point, if you want to book some time with me to discuss an artwork, why you like it, and how those insights can be helpful to you, then I’d be totally 100% down for that. I love talking about this stuff. I’m learning to be a creative coach, and I’m trying to find more clients. I went to two of the world’s best art schools—Central Saint Martins and The Royal College of Art—and I’ve been working in the creative space making art and writing for almost 15 years now. So I know a lot and I have a lot to offer :)

Anyway, that’s the first reason I love the crazy golf artwork so much and why it resonates with the type of work I wanna make. It’s uselessly useful all at the same time.

Now I want to share the second major reason that I love it.

2) Constraint sweet spot

The crazy golf artwork happens to fall in the sweet spot between too little and too much constraint. I’m not talking about the end users encountering constraints, but the constraints the artists encountered in the process of creating it. This issue of constraints has very big and important implications for you if you are a creator of creative things, so listen up.

For a while now, I’ve been trying to discern or pin down some first principles of creativity generally and of writing specifically. Probably just like you, I sense that our creative potential is subject to certain natural laws that, if we can only become aware of and learn to adhere to, can help us enormously—whether that’s getting inspired or getting unstuck.

This is still an early and unformed set of ideas, but to give you an example of what I mean by a first principle of creativity, one of them, I think, is the quality of our information diet, aka the stuff we’re allowing into our brains, together with the ways we’re choosing to ingest it.

If it was written down, that principle might say something like "nutrients in equals nutrients out” or “shit in equals shit out." And I'm thinking that if we know this is one of the basic principles of creativity, then we can refer back to it the next time we're feeling stuck. Maybe we're stuck because we simply aren't consuming enough of the right ingredients, and if that's true, that's useful, because then we can take corrective action.

That's an example of how I imagine this list of first principles working in practice. I don't think the list would need to be very long, just a few basic elemental things that, when taken together, constitute and govern our creative practice.

Back to my point about constraints: instinctively, I feel that constraints are a first principle of creativity too. Constraints have certainly played a key role in the production of the crazy golf artwork, which I’ll show you. But first I want to explain what I mean by constraints and why I'm suggesting they're first principle material.

I'm trying to think of examples we can all relate to. I'm sure you've been in the position where you procrastinated over a piece of work or an essay at school until it was absolutely too late to wait any longer, and you had to cram it all into one night, the night before the hand-in. That is constraints in action. Without that deadline, you may have waited forever.

And more than that, I've often heard people who did this say that cramming it all into one night's work, despite making them stressed, made them more creative or productive or whatever was important to them. Such is the mysterious power of constraint over our creative potential.

Another common example is when you have to make a meal using whatever's left in the fridge and in the cupboards. Usually, you can. And usually, you're quite happy with it. And it was a relief not to have to dig out a recipe and go shopping. There was something very focused and mobilising about making an omelette out of those three old eggs, the onion and half a pepper, the cheese that's on the edge, and sprinkling in some of those chives that are growing in the garden. Again, this is constraints lighting a path forward for you, reducing decision fatigue, and leading to the creation of something you would otherwise not have thought of.

Constraints work in mysterious ways. But ultimately, the reason I think they work is because it's often easier to push against something or work with something that's already there. It's easier to propel yourself through water when you've got the side of the pool to push off. It's easier to give editorial feedback on a piece of writing than it is to write the thing in the first place. And it's easier to make a piece of art when, instead of staring down the barrel of a blank canvas, somebody tells you, "It must do this and it must fit within a twelve-by-six square foot patch, and people must be able to walk around it and putt golf balls on it."

Just as we can refer to the quality of our information diet when we're stuck, I think we can refer to the level of constraint we've applied too—and then add more or less depending on what's needed—and make the whole process of creation feel a lot more enjoyable and productive.

There is probably always a sweet spot or an ideal range when it comes to constraints. The crazy golf course landed squarely in the middle, in my opinion. It was just enough constraint to mobilise and guide nine artists towards a unified idea, but not so much that it stifled them or forced them to work in a contrived way.

If the brief had consisted of too little constraint—if, say, they'd each been asked to design not a golf hole but a sporting arena of their choice—then one artist might have designed a tennis court while another designed a racing circuit, and the overall concept would have broken down and never achieved coherence.

If, on the other hand, the brief had imposed too much constraint—if, say, it asked them to work together to design one golf course by committee—then the nine artists would have probably bickered endlessly, created something less intriguing, and the public would have been left wondering who exactly designed what. Rather than a creative fusion, it would have become a confusion.

This is what I like so much about the golf artwork. The instigating artist seemed to understand that by leveraging a well-known structure together with well-understood conventions (nine holes, clubs and balls, person with the lowest score wins), they were giving the artists the perfect degree of constraint to operate within. And since there were nine artists altogether, and since each of them had total creative liberty to take their design in whatever direction they wanted, the constraints were delicately counterbalanced by a wonderful sense of unbridled freedom. The whole idea is beautiful! And I can only imagine what a joy it was to have been one of the nine artists commissioned to design a hole.

So how can these insights be useful? I think it shows a deep interest in the creative process. I think it shows that I personally love the creative process, and I want to understand it more.

I like the constraint principle particularly because, unlike so much of the creative process, it feels like something that you can actually control. Constraints are workable, like finding just the right setting on your adjustable spanner.

If there's something you want to do but you're struggling to do it, a little constraint tweaking could be all that you need. For example, if you say you want to write but you're not writing, then go back to first principles and consider whether you have too few constraints.

If so, then to dial up the constraints, you could choose a more specific topic to write about, or you could choose a day of the week to write on, or you could choose a strict word count to meet over and over. Or, you could use this app that deletes everything you've written if you spend too long dithering 😱 You could simply ask a friend to tell you what they want you to write about, or you could open a dictionary to page 147 and write about the third word on the left page. You could write something in the form of a letter to a friend. Or, I have a question for you: What if you wrote something that consisted entirely of questions?

On the other hand, perhaps the reason you're not writing is because you have too many constraints weighing you down. Maybe you're putting pressure on your creativity to pay your rent and feed your kids (that’s a lot of pressure!). Maybe you're filling most of your time and most of your head with other stuff like work, family, and hobbies, and you don't have enough time left to yourself. Maybe you want to make your creative project so perfect that it's stopping you from doing it at all. Or maybe you're just not giving yourself the permission to write a shitty first draft because you're constantly hitting the backspace key and analysing what you're creating before you've actually finished creating it. Far. Too. Much. Constraint.

If you want to be creative and make creative things, then you've got to control your constraints; they're your allies when you know how to marshal them.

To wrap up this second part then, I would say, take a look at any artwork that you like, or any song, any poem, any flower bed, or any cheese flan, and spend some time considering how constraints played their role—because they definitely did. Were there physical or functional constraints? Were they conceptual? Time-bound? Did they have to do with the materials used, the site or location? The people, or the skills or the perspectives involved?

Once you start examining creative work through the lens of constraints, you realise that the really good stuff grew from the sweet spot between too much and too little, and that consciously or unconsciously (but probably consciously), and either from within or from without, the artist, the writer, the musician, or whoever set the game up to win by steering a careful course between freedom and constraints.

By now, you've probably noticed that my first and second big reasons for loving the crazy golf artwork have to do with striking a balance between various qualities: uselessness and usefulness, freedom and constraints. In a similar vein, my third and final big reason I love the crazy golf artwork is that it manages to pull off yet another difficult and delicate balancing act—that between individualism and collectivism.

3) Individualism + collectivism

Can an artist truly collaborate? That's a good question. Self-interest, self-absorption, self-love—these, and many more like them, are all vital qualities if you want to be an artist and you want to make art. If you've ever wondered what the real difference is between art and design, it boils down to this: designers solve problems for people, whilst artists solve problems for themselves.

I'm not moralising or making any judgement calls whatsoever about any of this. I think it's actually crucial that all of us nurture our design tendencies and our artistic tendencies. I'm only making the distinction to point out one interesting characteristic of being an artist—that it can often be quite lonely.

And sometimes, depending on how sovereign you feel as an artist, it can seem like your primal need to shine and show your uniqueness can actually put you at odds with another human need with equally deep roots: the need to connect with others and to fit in.

Don't misunderstand me; I'm not trying to pathologize the experience of making art. I've already mentioned earlier that art-making and the lifestyle that surrounds it can be a luxury and a great privilege for many people. And I'm certainly not trying to make a case that artists are any more or less deserving of our thoughts or sympathy.

I'm just saying that every vocation has its trade-offs, and one of art’s trade-offs happens to be that making art can be a solitary endeavour, similar to that of the writer. And when you've tasted that kind of loneliness on a regular basis, it's not altogether pleasant. It's not something you look forward to as a feature of your long-term practice and lifestyle.

At the same time, for obvious reasons, artists need to protect their ability to think for themselves, to think of themselves, and it's in their best interests creatively and spiritually to maintain a level of autonomy and independence.

So, anything that gives artists the opportunity to be part of something bigger than themselves, whilst also encouraging and championing their individual expression, is always going to go down very well indeed.

Now you will understand that when I first heard about the crazy golf artwork, when my brain processed all the information in a nanosecond like brains are wont to do—”Wait! Nine artists? One prompt? Collective effort? Individual expression?”—I literally laughed out loud in joy, slapped my forehead, and pleaded, as you do with all great ideas, "Why the hell didn't I think of that?!"

It was the perfect artwork for artists, in my opinion. Your favourite artist’s favourite artwork. And I felt a strange fugitive wistfulness for the idea—an idea that seemed to tug at my heartstrings like the recent memory of a life-changing event I'd participated in, when the fact was, I played no part in it whatsoever; it had only seemed that way because it met so many of the criteria for what I think great art should be. I wished I'd been involved in making the crazy golf artwork so much that I actually ended up feeling as if I had!

Artists who are feeling lonely, or bored with “the self,” or who want to temporarily escape their own head and freshen things up by getting involved with a bunch of other creatives, can do so in this way. They don't have to sacrifice their own problems, interests, tastes, skills, style, or anything else in the process. They can find (or start) a project with a unifying idea, like a crazy golf course, an idea that is composed of several elements that would benefit from being treated individually and taken in disparate directions.

Think of things that come in batches: crazy golf holes, playing cards, furniture sets, book series, emojis, coins, banknotes, postage stamps, etc etc. Any one of these batched artefacts can be turned into a unified project and then given as commissions to a bunch of different creatives. Then everybody gets to have a great time. The artists get to be themselves to the limit. An old idea gets a new injection of energy. And we art lovers get to enjoy something unusual and cool—like a crazy golf course designed by nine different artists—and witness the rare symbiosis of group harmony and individual talent. There's almost something natural or preordained about the whole beautiful thing, the way it honours our seemingly divergent needs for connection AND significance.

I said at the beginning that I can't show you a picture of the crazy golf artwork because I've never seen it, and that's true if you can believe it. I could have Googled it at any time, of course, but I didn't—not because I'm dead against seeing it; I wouldn't turn away if you showed it to me, and I wouldn't refuse a game if you challenged me to it. I just never felt like I needed to see it in the flesh in order to enjoy it. It is enough as an idea alone for me to be satisfied thinking and writing about it.

I love that the artwork exists. I love that someone understood which levers to pull and how to get the most out of an idea and the people involved. It really is a masterpiece of boundary-blurring, balance, and sophistication—sophistication that you don't see immediately until you look closely, because it's hidden behind a veneer of popular culture and simple fun.

I'm a writer. And I'm impressionable. And now, after writing this, I want to follow in the footsteps of that artistic instigator by making a writer’s version of the crazy golf commission. I'm thinking, “What if I ask nine writers to respond to the same prompt?” I'm sure I would find willing participants (if you're interested, let me know!).

But the challenge would be in striking the right balance between the qualities I've written about here. I'd want the prompt to be both useless and useful, so that it gave the writers the right to write for writing's sake, as well as the responsibility of producing something the world needs. I'd want the prompt to be squarely in the constraint sweet spot so that the writers felt inspired and mobilised. And I'd want the prompt to appeal equally to the individual and to the group, so that the writers' resulting work demonstrated their unique brilliance along with their unity.

Ultimately, what I've learned by writing this piece, and by looking at great art and examining why I like it, is that the best art makes you smile. It makes you talk about it for years. It makes you sit down and write 5,000 words about it, if that's your thing.

Great art makes you want to make more great art yourself. And knowing which art you like, and specifically why you like it, makes you far more likely to actually go out and make it. And the world needs more great art.

So, what do you like?

See you next time folks

Harrison x

⬥

Thank you, Corina, for your feedback, and the original nudge to write this piece.

Want to read some more? My writing’s grouped by:

And you can read how this blog can help you here →

I absolutely love this piece Harrison! Everything about it.

It excites and inspires me to think about my favourite things, what makes them so, and why. And not just in terms of art, in other areas too!

Your choice of favourite artwork is fascinating ...I'm fighting an urge to search for it, yet I like that my own imagination is creating my own version!

I think it's your best piece yet! 😃